Writer’s Guild arbitrations are similar to lawsuits, in a way. Sometimes you’re forced into them against your will. All competing writers have an opportunity to present their case in a statement and there’s money at stake – credited writers split future residuals (uncredited writers get nothing) and usually a bonus is tied to whether or not a writer receives credit. In addition, a produced credit ups your asking price on your next job. (Usually. At least it used to.) In other words, there are stakes in this game worth fighting for.

Just like lawsuits that go to trial, the outcome is never certain. Three anonymous WGA members read all the material submitted by participating writers and independently reach a decision about who deserves credit and why. Majority rules. If there’s no agreement between the three, the Guild gets them all on a conference call until consensus is reached.

I’ve participated in several arbitrations, all of them stressful. The suspense ends relatively quickly – most arbitrations start and finish in two weeks or less. I’m a nervous wreck until the phone call from the Guild, informing me of the determination. So far I’ve prevailed in all of them probably because I walk away if I feel my claim for credit is less than rock solid.

I worried obsessively about the lawsuit referenced above, probably because – not being directly involved – I had no control over the outcome. As it turned out, J was right – my apprehension was unwarranted, nothing catastrophic happened. Our insurance companies settled things long before it went to trial. If we were served with a similar lawsuit tomorrow, though, I’d freak out again with fear we’d lose everything.

I worried obsessively about the lawsuit referenced above, probably because – not being directly involved – I had no control over the outcome. As it turned out, J was right – my apprehension was unwarranted, nothing catastrophic happened. Our insurance companies settled things long before it went to trial. If we were served with a similar lawsuit tomorrow, though, I’d freak out again with fear we’d lose everything.

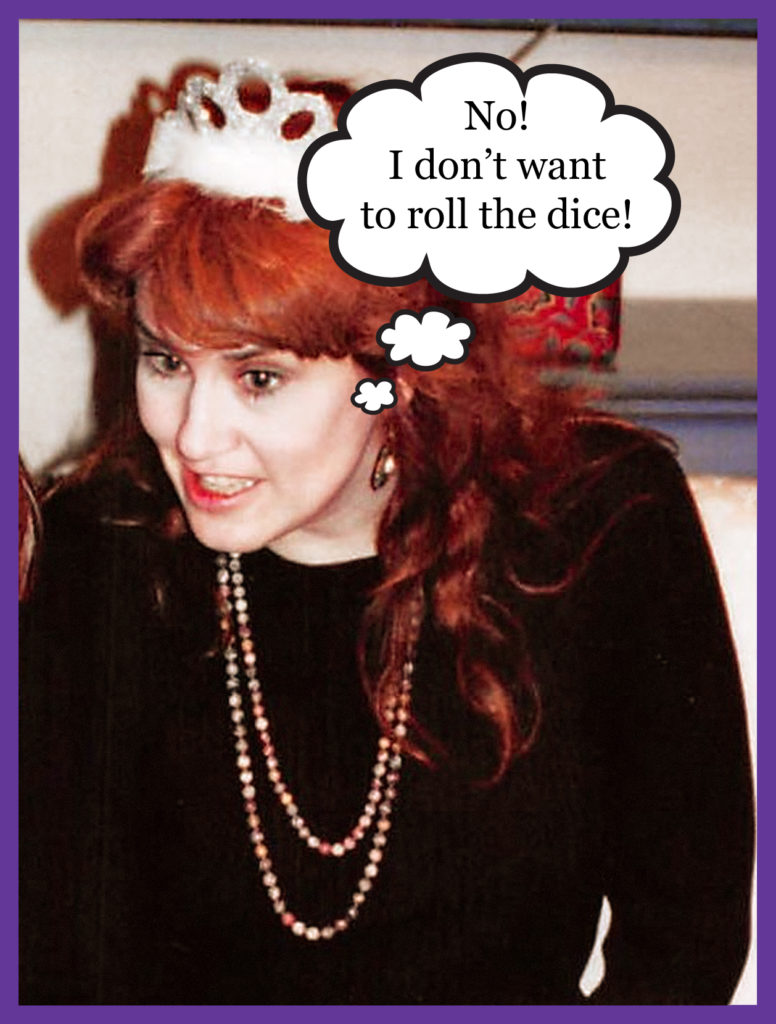

I would have made a terrible lawyer because I deal so poorly with uncertainty and ambiguity, the state in which all the trial lawyers I know live. “Doesn’t it feel good to roll the dice?” J asked me during one of my arbitrations.

No, it’s excruciating. It’s why I don’t gamble, either. I have to settle for J telling me it will be okay.

No, it’s excruciating. It’s why I don’t gamble, either. I have to settle for J telling me it will be okay.